Welcome to our second article about the backend architecture and its api gateway. In the first part, we talked about the BFF and all services it depends on. Today we’re going to take a look at what to do when one of them (or many), fails to respond.

Service dependencies

As seen previously, the BFF uses multiple data sources and services to create a full layout.

Those services are used to gather the contents to be displayed in the application:

- getting user personalisation data;

- advertising and analytics configuration;

- asking if the user has some authorizations.

If we don’t want our BFF to become one giant SPOF (1), we need to be resilient to the death (2) of those dependencies, any of them, at any time! You must keep in mind that our top priority is to always be able to answer something readable to the frontend applications.

DDD

First thing first, we are using a DDD (3) approach for our modeling. This means that we focus on the business, as described by our Product Owner. We try not to worry about the various implementation of our backend’s friends and their different services.

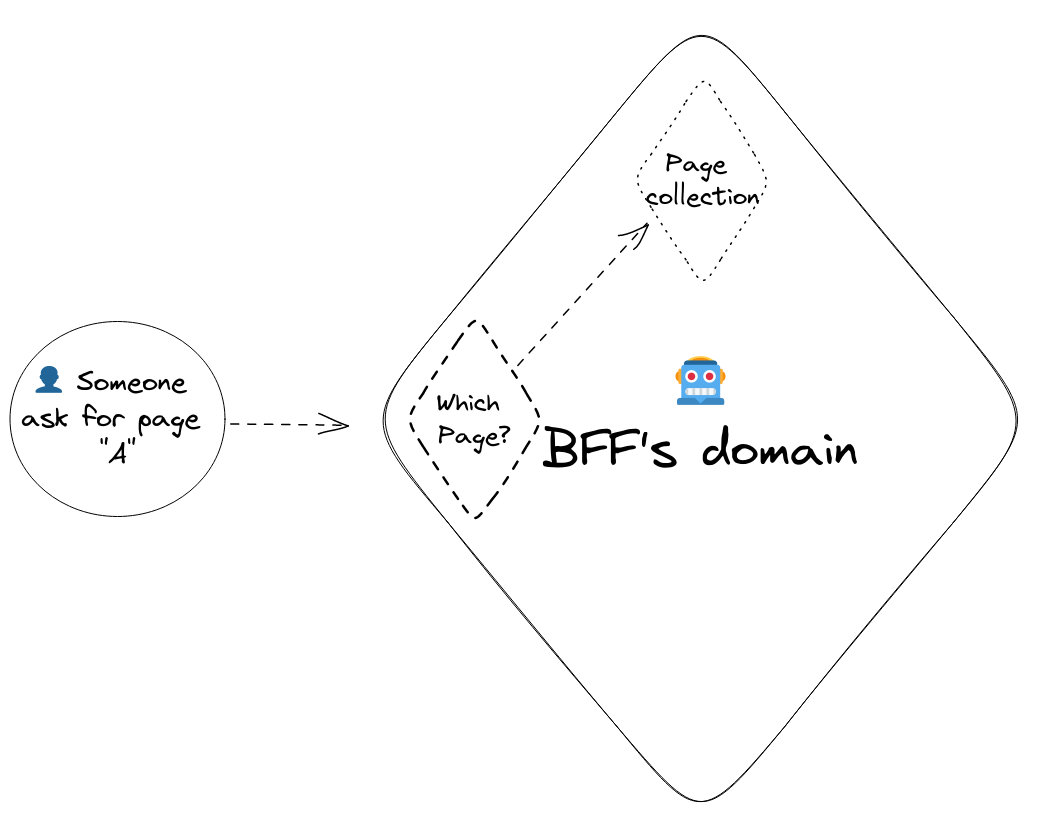

A picture is always easier to understand.

Above, we can see that when a user ask for a layout A, we are looking to resolve who is A.

From the domain point of view, the page collection is only an interface.

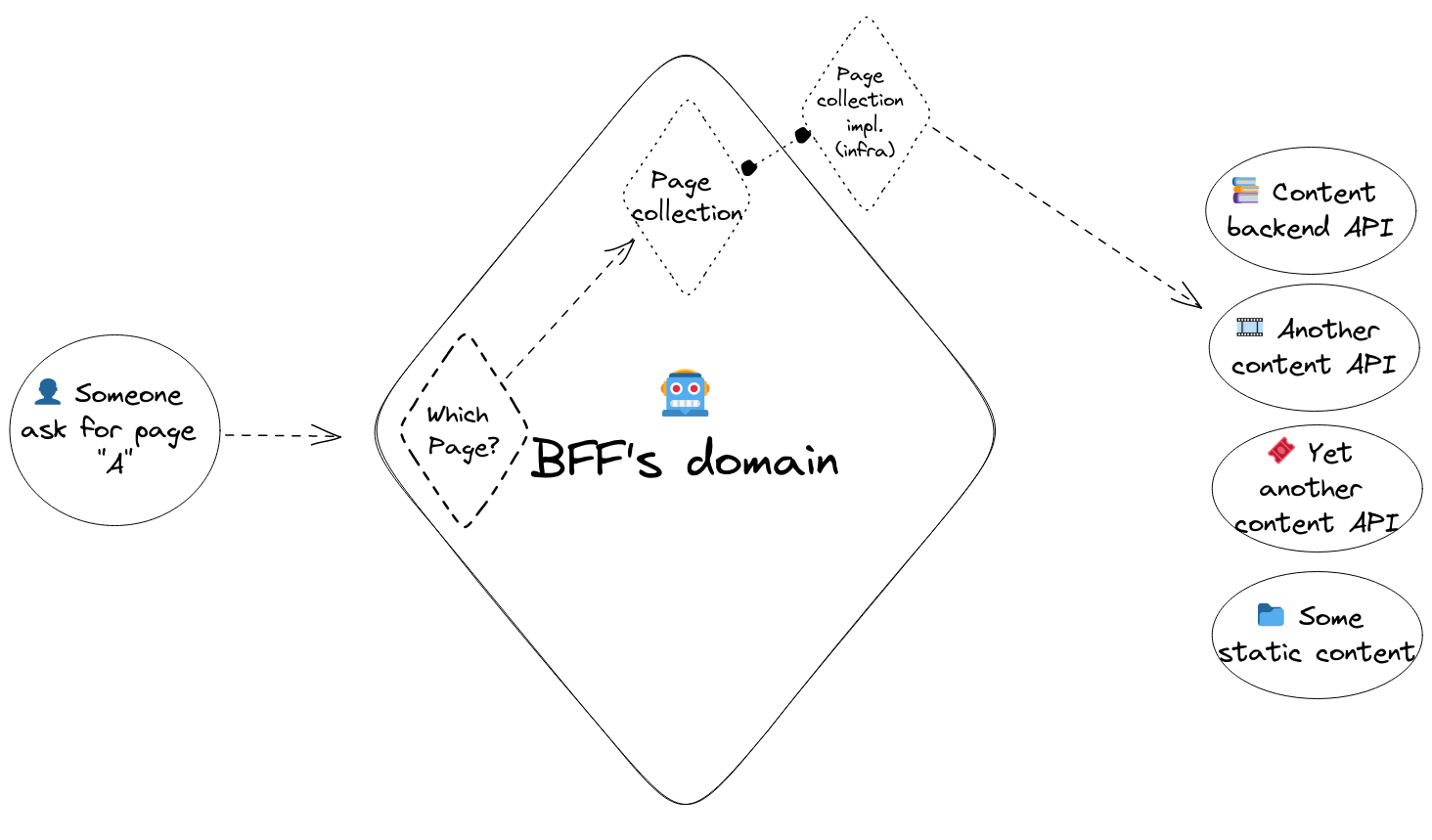

In the picture below, we see the “Page collection implem (Infra)”. It’s a layer implementing the interface defined in the domain. It uses multiple clients that call the services behind. It’s its responsibility to chose which service to look on for the page.

DDD is a too large subjects to be perfectly defined in this article. If you want to dig deeper into it, there are multiple great reads, feel free to check them out! Now, how does this help us?

Handling failures

Failures handling is done by the middle layer seen in the previous example. Its goal is to catch error (4), and convert them to something expected and defined by the interface.

That said, its responsibility is not to know what the expected answer is. To do that, we use the domain.

Let’s see with a small code sample.

Note: The following example is not a real use-case, but it’s representative and simple enough to illustrate how it works.

In the code below, we see a class that represents the subscribing status of a user, which has two properties:

hasAccesscontrols whether the user can read protected contents;isSubscribedis used in analytics, and to show subscription pages.

<?php

final class SubscribeStatus

{

private function __construct(

public readonly bool $hasAccess,

public readonly bool $isSubscribed,

) {

}

public static function createAnonymous(): self

{

return new self(false, false);

}

public static function createSubscribed(): self

{

return new self(true, true);

}

}

To create such an object, we use either one of the two static functions, depending on the status we get from the subscriptions API. This is done in the middle layer, but the business is kept in the domain.

To handle the failure, we add a new named constructor, dedicated to this specific case.

public static function createUnknown(): self

{

return new self(true, false);

}

When an error happens and we can’t retrieve the user subscription status, we now have a fallback option. With this fallback option, the user will:

- be able to access any content, it’s better to let an anonymous user access a content it should not, that blocking a paying customer;

- still be reported as not subscribed and will see all available offers.

Most of the time, the answer is even simpler than this one.

Another example would be user’s viewing statuses. If we can’t retrieve them, we don’t display any progress bar. Users won’t be able to tell if they have seen a content, but they will still be able to navigate the application.

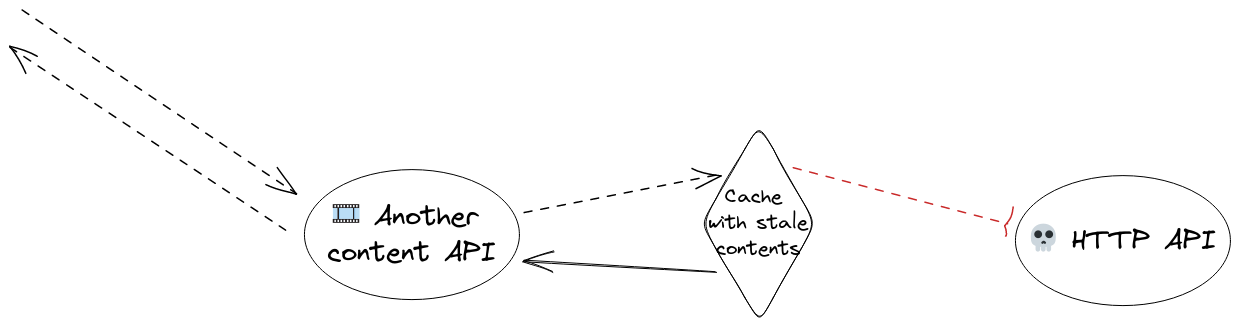

Infrastructure solution, the stale cache

In some cases, the above solution doesn’t work. For example, contents information cannot be replaced by default values. If we don’t know about a video or a program, we cannot guess what it is.

Luckily, we can rely on the stale cache. Stale cache is an old cache entry which is expired. When the cache finds such entry, it usually ignores it and asks for a new version of the response. In case of failure, we can use the available staled version.

The limitation is that a response must have been cached at least once, in order to have a staled version.

When there is no stale cache, we don’t display the content (5).

So far, we are only using it with http implementation:

- called API must answers with

stale-if-errorcache directive, it allows for the response to be used while stale when an error happens; - called API can answer with

stale-while-revalidatecache directive, for better performances; - calling API can query with

max-stalecache directive, to use stale response see the mdn for more on those headers; - on the client side, we are using the

Kevinrob/guzzle-cache-middlewareto do the job.

For an entry cached for up to 10 minutes (answered with max-age), we allow up to 4 hours of stale cache (with stale-if-error).

Since we are using a shared cache, we are using max-stale when querying, with a random value up to 1 hour.

This makes most requests use the last stale response while one of them ask for a fresher response.

Those values are chosen according to our platform usages where peak visitor last for about 2 to 3 hours at night.

We plan to expand its usage to other kinds of cached entries, such as manually saved data, and database queries.

Conclusion

In today’s post, we have seen how we handle the loss of our dependencies by anticipating their potential failures and preparing default acceptable behaviours.

Next time, we will see how we can spare some traffic on those dependencies when they’re struggling with traffic.

Notes

- SPOF, as single point of failure since all frontend applications have to rely on the BFF, I cannot resist linking this excellent xkcd.

- By “death”, we mean anything unexpected. It can be a 500 error code, a timeout, a wrong content. We will talk a bit more about this in the next article.

- DDD, as domain driven design, you can read more about it on Martin FOWLER’s website.

- Throwing errors is still allowed, but restricted to domain exceptions, and must be specified in the method’s declaration in the interface (i.e. via a comment).

- There will be a dedicated article on partial rendering.

From the same series

- What’s a BFF

- Handling API failures in a gateway

- What’s an error, and handling connection to multiple APIs

- Using a circuit breaker

In the meantime, feel free to have a look at other articles available on this blog: