At M6 we work hard to leverage Data to help our ad sales team, our CRM teams and our product innovation process. Over the past 2 years, we have gone from using a market DMP to creating our second Hadoop platform. We now feel that our stack is stable, reliable and scalable so it feels like the right time to share our experience with the community.

Step 1: embracing the DMP

Our first use case was to monetize data through targeted publicity. We decided to start by installing a DMP (Data Management Platform) because it was a very fast solution to deliver our major needs, in particular :

- Collect data from all our services and combine it with our user knowledge => DMPs offer that off the shelf

- Create segments for audience targeting => The segmentation approach offered by DMPs was well adapted to the ads market

- Activate our Data, both in house via our adservers and in the outer market => DMPs generally offer simple integration with most adservers, and a very straight forward third party integration

The match seemed quite obvious and there’s a good reason for that: DMPs are designed for this use case above all others.

We chose Krux (now Salesforce) and deployed it over our ~30 sites and applications. Installing Krux on our network and plugging it to our video and display adservers ended up taking a few months and a decent effort. Convincing all our teams that the increase in ad revenue would make it worth the development time and the negative impact on webperf wasn’t trivial, but got through thanks to our top management sponsoring. Once on the job, the deployment was quite smooth on the web and mobile apps, but validating the quality of the ingested data turned out to be an endless project.

At the end of the day, Krux’s DMP did the job. In November 2015 we launched Smart6tem, our Data platform & advertisement offer based on segments (announcement here, articles here here or here). This move had a very positive effect on our advertisement market, and allowed to start making Data mean something at M6. To give some detail of our use of the DMP, it turned out building our own segments was very successful, but we didn’t use any 3rd party interconnection because we didn’t find any valuable Data to buy and didn’t want to reduce the value of our own Data by sharing it out.

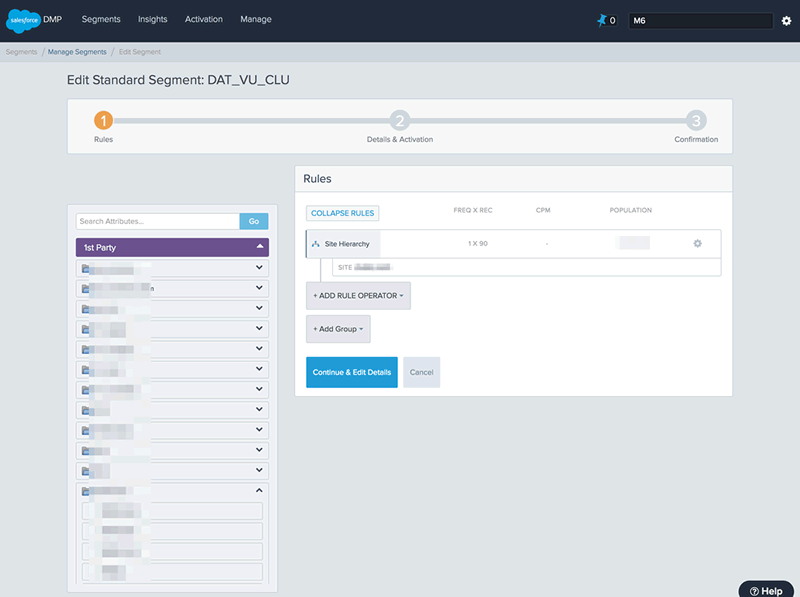

Krux’s segment builder

Once the Advertisement use case was out in the market, we moved our efforts towards leveraging the DMP for our CRM teams. The rationale was simple: targeted emails are more efficient than newsletters. We were hoping to reduce the email pressure on our users while increasing the performance both for revenue and traffic.

Step 2: first round testing Hadoop

Having a DMP is both a great accomplishment and frustrating. It’s great because you can start to combine the use of your service with the user profiles to produce segments and activate use cases to address them. But for CRM, the workflows to plug segments into our emailing systems weren’t native and we needed to build some custom workflows. No rocket science, but when we first received a 2 Billion line file for the user/segment map that we needed to filter and convert into another format, our developers went grumpy. We also got frustrated very fast because we wanted to start to extract some unpreceded analytics insights combining our user knowledge (our major service, 6play had just switched to fully logged-in users) with usage stats or with external sources like our adserver logs. Advanced analytics was clearly not the field of Krux. Last but not least came some limitations (either due to the design of Krux or the pricing):

- We could only work on 3 months of history if we wanted to keep the price reasonable (on 6play we have a lot of TV shows that run for 3 months per year, and segmenting the users who watched the show last year is important).

- It’s based on cookies + device ids on mobile (it’s the best solution for most use cases, but if your users are logged in, it introduces quite a lot of risk to make mistakes).

- We never managed to convince our users that the amount of cookies or users inside segments was correct. Every single study we made on this point led to doubt, and our DMP support team never came up with serious answers.

At this point, Hadoop came in as an evidence, so we created our first cluster. The process of creating this proof of concept cluster was pretty much a black box for us since we charged a partner with the job. We ended up with the following setup, all hosted by AWS :

- 2 name nodes with 16 VCPUs and 30G RAM each

- 4 data nodes adding up to 64 vcpu’s and 120G RAM

- Cloudera Enterprise with Hive, Impala, Hue, Python, R and a kinky crontab

- Tableau Desktop + Tableau Server

Nothing crazy but that brought us into the world of Hadoop, and that was a major move. We also staffed our first Data Scientist to start to explore our Data and imagine use cases.

Our first steps in Hadoop were hesitant, but within a few months, we had created our first Data Lake, our targeted CRM was live and we had produced a few dozen dashboards providing unpreceded insights throughout the company. From the business perspective, it was a success. For the people who got their hands on a Data Lake for the first time the experience was ground breaking. For the first time, we could connect information from half a dozen different tools seamlessly. An example: finding how many ads were seen by women from 25 to 49 years old during the NCIS TV show. Before the Data Lake, this would have been impossible. The closest we could get would take the following process :

- Extract the amount of ads viewed on NCIS from our adserver stats to a text file

- Extract the NCIS traffic from our video consumption tracking tool (in Cassandra) to a text file

- Extract our users Database with age and gender (in a third party tool named Gigya) to a text file

- Load all this up into an Excel spreadsheet

- Write a bunch of Excel formulas to produce the percentage of the traffic on NCIS that’s generated by women between 25 and 49 years old

- Apply that percentage to the adserver stats

As you can see, combining information between our ecosystems involved some very manual processes and could only lead to approximations, so basically we never did them.

With our Data in Hadoop, all this turns out to be a simple SQL query in Hue (a PhpMyAdmin style interface for Hadoop):

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM adserver_logs A

JOIN users U ON A.uid = U.uid

JOIN programs P on A.pid = P.id

WHERE A.type = 'impression'

AND U.age >= '25'

AND U.age <= '49'

AND U.gender = 'F'

AND P.name = 'NCIS'

Hadoop and our Data Lake, we could just jump over the barriers between tools and ecosystems within seconds. Combined with the ability to code in various languages, we could instantly start to industrialize such insights and start going further.

We convinced our top management very fast about the value of having our own Hadoop cluster, and since it was very (VERY) expensive, we decided to internalize it.

Step 3: building our internal Hadoop cluster

So there we were with a quite simple roadmap: replace our v1 Hadoop cluster to reduce costs and improve performance as much as possible. We managed to divide the price by 3 while multiplying the resources by 8.

The first step on this road was to staff a tech team to design and create our platform. That ended up being very tricky and finally took us 10 months to complete.

Once the team was staffed, we got onto the job. We had 5 steps :

- Choose the hosting platform (4 months)

- Choose the hardware

- Choose the software stack (2 months, done in parallel)

- Set up the cluster (2 months)

- Migrate all our projects to the new platform (3 months)

- Check to be sure everything was done (1 month)

a) Hosting platform

This stage of the project was a very religious one. Many people at M6 had a very strong desire to go towards cloud and managed services, others were totally in favor of Hadoop and have full in house control over the platform. The major options were:

- AWS

- Amazon EMR + S3

- Amazon EC2 + S3

- Google Cloud Platform

- Managed services (Dataflow, BigQuery, Compute engine, Pub/Sub…) + Cloud storage

- Dataproc + Cloud storage

- On premise

- Add servers to our 6play platform at Equinix

- Work with our hosting subsidiary, Odiso

We spent 3 months talking to the different vendors and considering options.

The first decision we took was to use Hadoop instead of managed services. The AWS and Google sales teams were very convincing, but we finally declined for 2 main reasons:

- People in our company were starting to learn how to use Hadoop, changing the stack would have forced everyone to re-learn what they were just starting to dominate. Not very efficient while building up expertise.

- Using proprietary solutions like Big Query involves a strong locking risk. If we developped all our projets to leverage a specific platform, changing providers in a few years would involve a lot of reworking on all our code base.

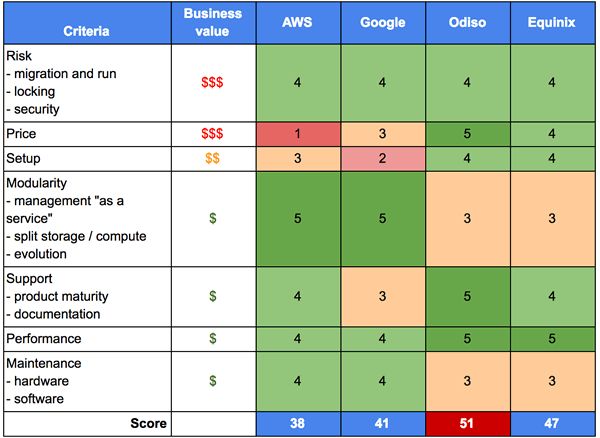

The next step was to choose between the 3 hosting options. On a side note, we compared the price for x4 and x10 resources compared to our v1 platform. At the end of the process we wrote up an evaluation grid. Here is the summary version.

The decision was there, we went for a fully on premise stack with Odiso. To detail some of that evaluation, here’s a few insights on what it came down to.

- AWS is cool, but ultra expensive. I mean it’s 10 times more than our on premise option! We would have gone full AWS if the price was reasonable. The possibility to pop clusters up and down is very interesting and reduces costs, but our v1 platform was using our 4 EC2 Data Nodes at ~80% 24/7, so we could never go down to 0 servers.

- Google feels better on the service side of things, but it involved taking chances because the commercial product is young and support + community experience seemed weak.

- On premise was clearly much cheaper, and felt more secure for our low experience on Hadoop since we’re used to managing servers and our team had managed serious Hadoop before.

b) Hardware

Going on premise means buying physical servers and building them. Our goal here was to massively upgrade our current platform to scale with the company’s usage of Big Data. Since the price was very reasonable, we settled down to x8 on CPU, RAM and storage compared to our initial Hadoop cluster. Here’s the stack we bought:

4 KVM servers:

- DELL PowerEdge R630

- OS Disks: 2x 400GB ssd, RAID 1

- Data disks: 8 * 2To

- RAM: 256Go (8*32G)

- CPU: 2x12 Cores (3.0Ghz)

15 Data Nodes:

- DELL PowerEdge R630

- OS: 2x 400GB ssd, RAID 1

- Data disks: 8 * 2To

- RAM: 384Go (24*16G)

- CPU: 2x12 Cores (3.0Ghz)

Building and racking the servers was quite straight forward, there’s nothing special about Hadoop in this process except the high quality network connectivity.

c) Software stack

Designing the software stack was very straight forward. We had the desire to stay as close as possible to the stack our users were getting used to, and it was pretty much a standard Cloudera stack. That suited us very well because our first priority was to avoid any regression, both for the projects (during this period, they had massively multiplied as we’ll detail in the migration part below) and for the users. Another early choice was to use virtual machines with Proxmox and not dive into the Kubernetes + Docker adventure. Although that was tempting and will probably be an option in future, we considered mastering the Hadoop stack was enough on our plate for the moment, we needed to reduce risk.

Here’s the stack we chose:

- Puppet

- Centos 7

- Proxmox

- Cloudera Hadoop 5.11 (free version)

- Hadoop 2.6

- Hive 1.1

- Spark 1.6 and 2.1 (we had 1.6 before but our Data Scientists really wanted to use new features)

- Supervisord

- MariaDB

- LDAP

- Ansible

- OpenVPN

- Python 2.7 and 3.6 with Anaconda

- Java 8

- R 3.3

- Scala

- Airflow 1.8 (this is out of the Cloudera stack, an important and epic part of our toolkit that we’ll surely talk about in more detail in a future post)

- Sqoop

- Hue 3 with Hive on Spark as default

- Tableau Desktop + Tableau Online

- Jupyter

d) Install Hadoop and all our tools

One of the fun parts of our design process was to choose a name for our new cluster. We called it Cerebro (in reference to X-Men and the global view of Professor Xavier), and created a logo :)

Setting this stack up felt very simple from my perspective, but that’s surely because our awesome team overcame the issues silently. On the timeline, the biggest part of the setup was receiving the physical servers. That took about 3 months because some parts (SSD disks) were out of stock for a long time. We received a first part of the Data Nodes a couple of months before the rest of the servers, so we decided to start building the cluster with temporary Name Nodes and services, and migrate them after.

We deployed Cloudera Hadoop via KVM servers (managed with Puppet) and the Cloudera Manager. Very straightforward. We used Ansible to install our stack, manage all our configuration files and user access.

e) Migrate our projects and Data

Migration was a project in the project. Between the day we decided to build our internal platform and the day we delivered, 20 months had gone by. During all that time, Big Data had been going through high pace growth inside M6. We scaled from ~1 to ~25 users, from 0 to ~200 Dashboards and ~60 projects. All of this relying on our “Proof Of Concept” platform created with a partner. To be honest, it was an utter mess in any Software Engineer’s eye. Imagine: no version control, a unique user hosting all the projects and executing 6000 crontab lines each day. No job optimisation whatsoever. Moreover, most of our users had no developpement process knowledge, so they didn’t see any problem with all this and weren’t all in favour of any change. The context was challenging.

The first step of our migration project was to bring all this back into a “migratable” state. To do that, we went through the following steps :

- Put all the code base in Git

- Create a code deployment process

- Split the production jobs down to a 1 user per project approach, both for code execution and data storage

- Make all paths to data relative

- Switch from crontab to Airflow

- Add backups on S3

We reached this milestone after 4 months of a large rework of all our projects by all our teams. The collective investment in this process was a real team success.

The second step was to rebuild all the projects and databases on the new platform. Thanks to our new backup system that copied all our Data to S3, rebuilding databases was easy. Basically it took creating a script to restore the backup in the new platform, and we could start checking integrity by querying the datasets. Rebuilding projects was a similar process, we just had to deploy each project and it was ready to test. Everything went fast and easy, proving that all the preparation moves we made were very valuable.

The third step was to double run all our projects so we could be sure everything worked on the new platform while not breaking production. There’s a tricky part to this because a fair amount of our projects include an output towards external servers (either other teams within M6 or 3rd parties). For this we had to add an “only run on” logic. That lead us to create a unified configuration and a library for exports. We also had to distinguish all our code execution monitoring so we could keep an eye on what each workflow was producing, both in production and on the new platform. For this we added the platform name to all our Graphite nodes and updated all our dashboards to filter by platform. With those 2 moves, most projects managed to run “out of the box”. Some needed some refactoring, mostly for parts that had been forgotten in the first step.

The fourth step was validating that our double run was working well. The theory of this validation was quite elaborate. For each table or output job we would count the number of lines in each partition produced, run checksums, dive into the details of the monitoring, and run manual tests. In practice, that part cracked up quite fast because our v1 platform was being totally outscaled and therefore all our users really didn’t want to look back. We checked that the backups were good with file sizes and line counts, and for the rest we relied on our monitoring to be sure that the jobs runned and produced the same output volumes. For the most critical production jobs we went into some detailed manual checking, but we took the jump very fast.

The fifth and last step was migrating all our Tableau Dashboards to Tableau online. We needed all our ingestion and treatment jobs to be up and running before we could migrate our 200+ Dashboards. Once that was done, most dashboards took nothing more that being opened in Tableau Desktop and published to Tableau Online. The only exceptions were the bunch of users who had missed some tables out in step 1. Those had to run through the whole process at fast speed… Not very pleasant for them.

So there we are, we now have our 2 feet in our second Hadoop platform. Now we’re looking forwards, both on how we make this platform evolve to empower our future use cases, and to raise our innovation pace for Big Data to count much more within M6. By all means stay posted, we’ll update you on some of the awesome projects we’ve been working on!

Take away

- Deciding to create an internal Hadoop platform took time and a few previous steps for our organisation to start to understand what Big Data was about and the way to go around it.

- Choosing our hosting solution was hard and very conviction driven.

- On premise hosting is cheaper than cloud solutions, but obviously less flexible.

- No surprise for tech people and it’s valid way beyond Big Data, migrating projects developed without any engineering good practices was hard and risky work.