During the UEFA Euro football cup in June and July 2024, M6 broadcasted several matches. Of course, this competition was available, live, on M6+. For every user joining right from the first second and or for all users hearing their neighbors shouting and wanting to re-watch the action, starting a live video stream had to work!

When you use one of the platforms we manage, your goal is to start a video stream. You land on the homepage of a platform like M6+ or Videoland, browse the catalog, register or login and, ultimately, you’ll start a video. It’s the one thing that causes the most frustration if it fails. And we don’t want that. We want users to enjoy their experience.

For Euro, we first worked on shortening the browsing part, to both provide a great experience for users arriving to watch a match, and to lower the load on our platform. We talked about this in How Special Event Page allowed us to handle more than 1 million of users.

We also worked on reducing load on our backend applications, allowing our platform to handle far more users and load than it’s used to. This post is the story of how we used compute-at-edge for the first time!

Our backend platform

All our frontend (web/mobile/TV) applications communicate with our backend components through what we call BFF. This BFF then calls many other backend APIs and returns a layout that contains everything an app needs. This layout will contain lists of rows and blocks when you are browsing the catalog, or most information required to start a stream when you are trying to do so.

With this architecture, BFF receives a lot of requests, and each of these causes up to dozens of requests to other services. This is greatly amplified by the fact that all BFF responses are personalized, which means we cannot cache entire responses.

As most of our APIs are running in a Kubernetes cluster, you might say “use auto-scaling!”, and you’d be kind of right. We are using auto-scaling. But reactive auto-scaling, based on traffic or load metrics, is not fast enough to handle huge spikes in traffic – like big football matches can cause. For this, we have developed a pre-scaling mechanism, and even open-sourced it.

But we didn’t want to take any chances…

Disabling all personalization?

First, a word about an idea we used three years ago: disabling all personalization. It’s quite easy to implement: ensure BFF doesn’t do any personalization work, and return a cache-control HTTP header so the CDN in front of the BFF backend application caches layouts and returns them to all users.

With BFF only generating a few dozen responses every minute, we solved all possible problems with load or scaling and traffic spikes. But this also means cutting many features for end-users, and not displaying personalized ads.

Our customers want to display personalized contents and ads, and users want to get all features from the platform. So, we decided not to enable this mechanism this year.

Doing more work… in front of the backend app!

Several months before the Euro competition, one of our Principal Engineers had done a few prototypes with Fastly’s compute and datastores at-edge, convinced being able to do more things before the apps would one day prove useful. Well… We brought back this idea to focus. And our BFF application was already using Fastly as its CDN, what a coincidence ;-)

- Fastly allows one to run compute at-edge, on the CDN points-of-presence. Basically, you write code in Go/Rust/Javascript and compile it to WASM.

- It provides several datastores. The one we used here is called KVStore – a basic key-value store.

We reworked our architecture this way:

Our goal was to implement a lightweight personalization layer in front of our backend BFF application. The backend application would then only need to return non-personalized layouts – and those would be cacheable.

Note: as we have many frontend applications and did not want (and did not have enough time) to update all of them, we searched for a solution that would only require changes somewhere on the backend side.

This personalization layer would read some basic data (does the current user have a subscription? Did they consent to tracking and analytics?) from a datastore-at-edge and use them to inject identifiers in the cached-non-personalized layout before returning it.

As BFF was already using a Fastly VCL service as its CDN and a VCL service cannot also do compute, we decided to insert a compute service between the VCL one and the backend, only for the /live/ route. As time was limited and we wanted to confirm how this would work with real users, we chose to implement this approach only for one route and one layout, the one that would be called the most: the layout used to start a live stream.

This means our CDN architecture was looking like this:

VCL] fastlyVCL -- /live --> fastlyCompute fastlyCompute[Fastly

Compute] datastore[(Datastore)] fastlyCompute -.-> datastore end fastlyVCL -- /* --> bff fastlyCompute -- "read

(with cache)" --> bff bff((BFF))

Before starting to actually implement this, we talked with our contacts at Fastly, to confirm this approach made sense to them and their systems would be able to handle the load and traffic spikes we were expecting. They validated the concept, and noted we should shard our data over several KVStores, as each KVStore is limited to 1000 writes/second and 5000 reads/second – good catch!

We then started implementing this approach, first with our compute-at-edge code doing static replacements, then with loading random data from the KVStores, and finally with loading the real data. Between each step, we ran synthetic load-tests, to ensure everything was running smoothly.

Also, we ensured from day-1 we would not have to throw all this “do more work in front of BFF” approach away, if Fastly was not able to handle our needs. We had a fallback in mind: deploying this inside our Kubernetes cluster as a Go application and storing data in DynamoDB. Most of the code would still have worked.

Getting the data to the datastore-at-edge

Reading data from KVStores and using it to personalize the live layout being out of the way, it was time to think about how to get data into those KVStores.

We had to synchronize pieces of data from two different backend APIs to the at-edge KVStores. First is our “users” API, for GDPR consents. And the second is our “subscription” API. Both store their data in DynamoDB.

Several months before, one of our Principal Engineers had done a few demos and prototypes showing how to use DynamoDB Streams and Lambda the right way and proving asynchronous is not necessarily slow. This helped not start from scratch here, having confidence working with DDB Streams and Lambda would be OK, and providing some code foundations.

So, in both “users” and “subscriptions” projects, we added a DynamoDB Stream on the tables used to store the relevant data. Those streams are read from a couple of Lambda functions (with retries, batches bisect, dead-letters queues… all natively handled by AWS). And those functions call Fastly’s KVStore API to insert/update/delete data there. We did not forget to deal with the 1000 RPS per KVStore limit.

Stream --> lambda2 lambda2(Lambda) end subgraph "API-4 (AWS)" api4[API-4] ddb4[(DynamoDB)] api4 --> ddb4 ddb4 -- DDB

Stream --> lambda4 lambda4(Lambda) end lambda2 --> datastore lambda4 --> datastore subgraph "Fastly CDN" datastore[(Datastore)] end

With this mechanism, data in the KVstores is updated after 1 or 2 seconds (we could speed things up a little by not using batching when reading from DynamoDB Streams), which is fine for this use-case.

In addition to this synchronization mechanism, we also implemented a full import process, used to initialize data for all users and subscriptions – and to fix a few edge-cases with odd data we didn’t anticipate.

Better resiliency

Looking at the architecture schema shared before, one of our Principal Engineers noticed if the BFF backend component is down (possibly because of an overload caused by too many users browsing the catalog), it will not return non-personalized layouts. And Compute, at-edge, will not be able to do its personalization work.

So, we chose to asynchronously pre-generate the non-personalized layouts, and store them on Amazon S3. S3 would then be used as origin by Fastly Compute.

VCL] fastlyVCL -- /live --> fastlyCompute fastlyCompute[Fastly

Compute] datastore[(Datastore)] fastlyCompute -.-> datastore end fastlyCompute -- "read

(with cache)" --> s3 s3[(S3 Bucket)] fastlyVCL -- /* --> bff bff((BFF)) bff -- "Generate static

files every X minutes" --> s3

Of course, doing this requires a bit more development work. We’ve had to setup a background cronjob to generate static layouts and store them on S3. But, keeping in mind our “users must be able to start a stream” goal, we estimated the potential gain on resiliency was worth it. Also, we already had a process to generate static layouts and push them to S3, so it wasn’t that much additional work.

The Special Event Page helped ensure users would not have to actually call most our backend APIs at all between the homepage and starting a live stream.

Load-testing and real life

We carefully load-tested this solution, every step of the way while implementing it. Once fully implemented, we load-tested it again and again, to ensure it would handle as much traffic as we were expecting to get during high-stakes matches.

Doing those load-tests and analyzing their results with our contacts at Fastly helped us identify three points we quickly fixed:

- At first, our KVStores’ primary location was in the US. Fastly reconfigured our account to have them primarily located in the EU, gaining several dozen milliseconds of latency each time new users would do their first read.

- We compiled our Golang code to WASM with both Tinygo and Biggo. One produces WASM that used more CPU, and the other produces WASM that used more RAM. In the end, we followed Fastly’s recommendations, considering they know better than us what resource could be a bottleneck for their platform.

- The first time we ran tests in our production environment, results were not great. Far worse than in our staging environment, in fact. Well, we had not paid for the Compute option in our Fastly’s production account yet, and it was configured with lower rate-limits than in staging 😃

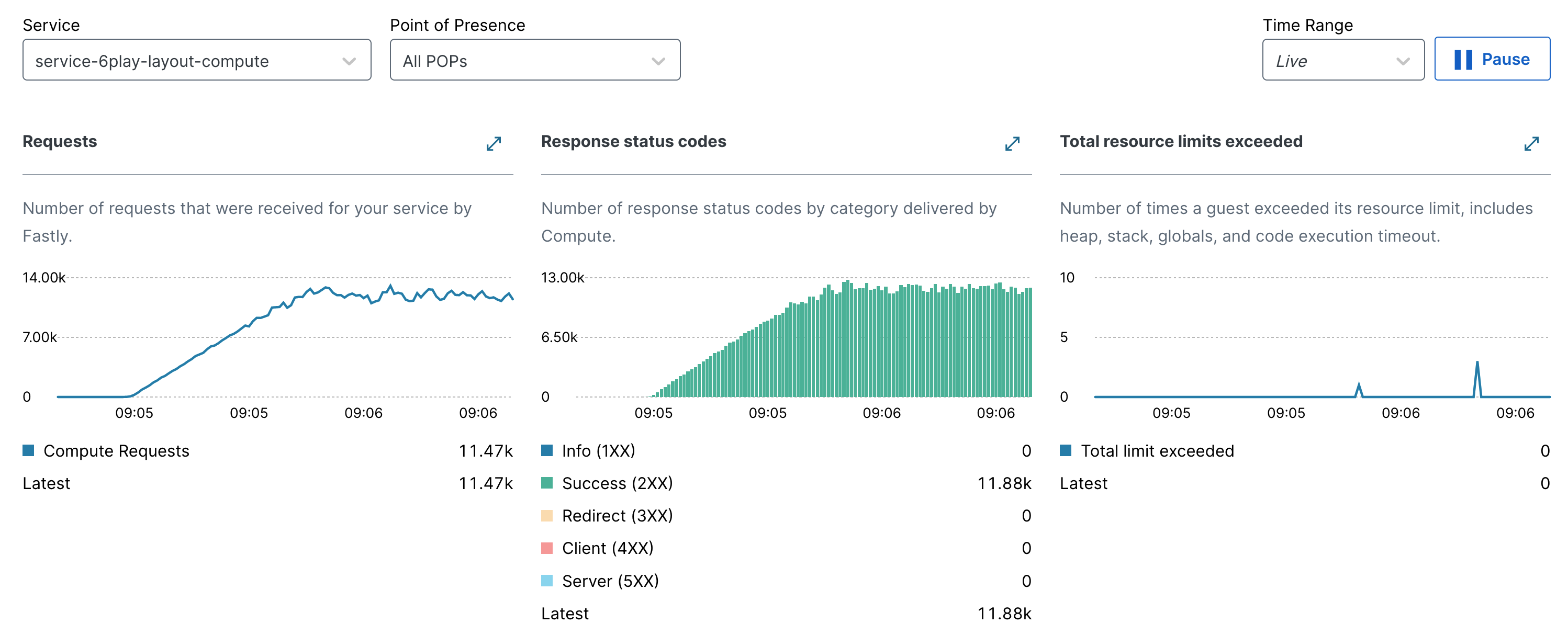

During these load-tests as well as during real events later, we monitored a few basic metrics: number of calls per second, CPU and RAM usage, latency and error-rate.

The high number of requests-per second we reached during our load-tests proved Fastly Compute is a viable approach for this workload, and for some others we are already thinking about migrating.

On our backend’s application side, we also checked the number of calls per second was going down while it was going up on Compute at-edge. In practice, it went down to 0 for the /live/ route, and remained stable or even went up for other routes, as there were more users browsing the catalog.

Conclusion

With this approach to generating personalized layouts at-edge for the /live/ route, users of our platform have been able to enjoy the competition without any hiccup!

- We personalized millions of live layout on the CDN at-edge, using Fastly Compute, enabling both users and customers to experience pretty much all features of the platform.

- Our backend BFF and other APIs have not been overloaded. They have been fully operational to serve requests for users browsing the catalog or starting videos on demand.

And this proved edge computing is a viable option to implement some features of our platform. More than this, though, it proved we can separate our BFF software into several smaller parts, which is one of the major ideas we will implement next year while re-architecturing it.

What are the next steps, then?

- First, use Compute at-edge to serve a couple other highly-solicited routes.

- And, for the

/live/route, implement a few use-cases that were not required for this competition, in order to use Fastly Compute for this route all the time!