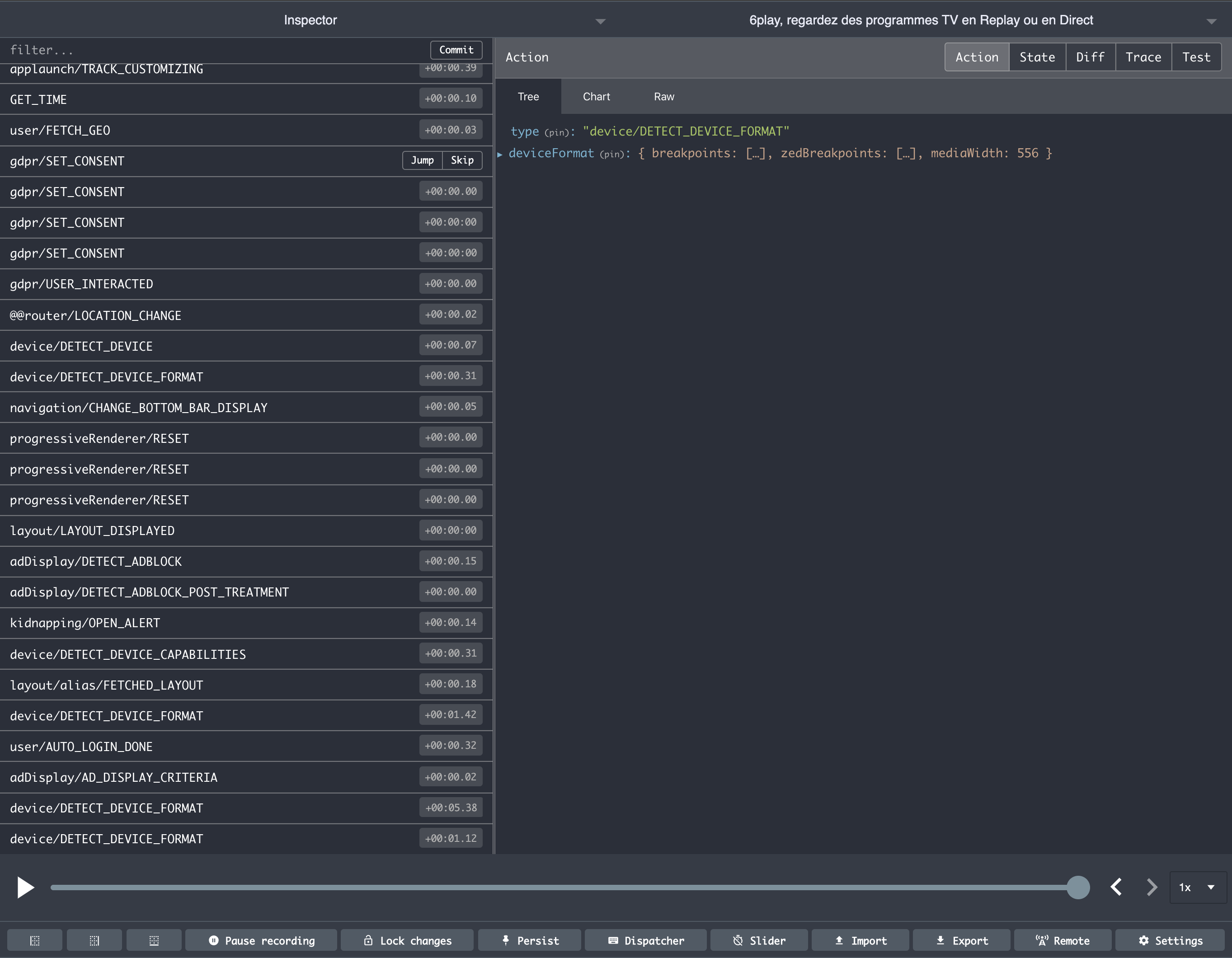

After 2 years using React with Redux for the video platform 6play, I was able to identify good practices and pitfalls to avoid at all costs.

The Bedrock team kept the technical stack of the project up to date to take advantage of the new features of react, react-redux and redux.

So here are my tips for maintaining and using React and Redux in your application without going mad.

This article is not an introduction to React or Redux. I recommend this documentation if you want to see how to implement it in your applications.

You could also take a look at Redux offical style guide in which you could find some of those tips and others. Note that if you use the Redux Toolkit, some of the tips/practices presented in this article are already integrated directly into the API.

Avoid having only one reducer

The reducer is the function that is in charge of building a new state at each action.

One might be tempted to manipulate only one reducer.

In the case of a small application, this is not a problem.

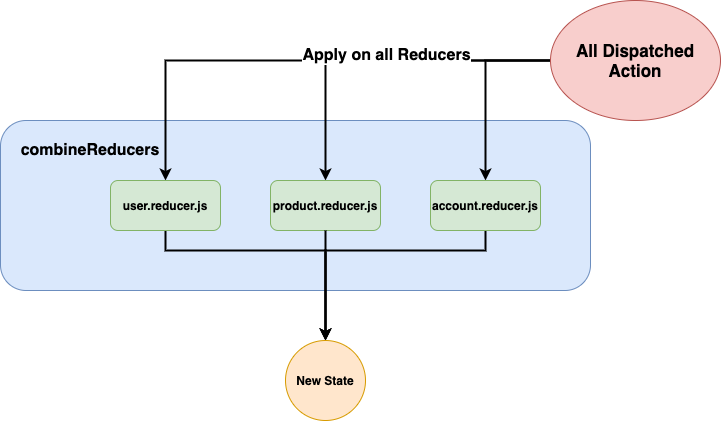

For applications expressing a complex and evolving business, it is better to opt in for the combineReducers solution.

This feature of redux allows to manipulate not one but several reducers which act respectively on the state.

When and how to split its application?

What we recommend at Bedrock is a functional splitting of the application. In my approach, we would tend to represent the business of the application more than the technical stuff implied. Some very good articles explain it notably through the use of DDD principles.

In Bedrock, we use a folder named modules which groups together the different folders associated with the feature of your application.

app/

modules/

user/

__tests__/

user.reducer.spec.js

components/

user.reducer.js

product/

__tests__/

product.reducer.spec.js

components/

product.reducer.js

account/

__tests__/

account.reducer.spec.js

components/

account.reducer.js

store.js

index.js

So in store.js all you need to do is combine your different reducers.

import { createStore, combineReducers } from 'redux'

import { user } from './modules/user/user.reducer.js'

import { product } from './modules/user/product.reducer.js'

import { account } from './modules/user/account.reducer.js'

export const store = createStore(combineReducers({ user, product, account }))

By following this principle, you will:

- keep reducers readable because they have a limited scope

- structure and define the functionalities of your application

- facilitate the testing

Historically, this segmentation has allowed us to remove complete application areas without having impacts on the entire codebase, just by deleting the module folder associated with the feature.

Proxy access to the state

Now that your reducers have been placed in the functional module, you need to allow your components to access the state via selector.

A selector is a function that has the state as a parameter, and retrieves its information.

This can also allow you to select only the props needed for the component by decoupling from the state structure.

export const getUserName = ({ user: { lastName } }) => lastName

You can also pass parameters to a selector by wrapping it with a function.

export const getProduct = productId => ({ product: { list } }) =>

list.find(product => product.id === productId)

This will allow you to use them in your components using the useSelector hook.

const MyComponent = () => {

const product = useSelector(getProduct(12))

return <div>{product.name}</div>

}

It is specified in the react-redux doc that the selector is called for each render of the component.

If the selector function reference does not change, a cached version of the object can be returned directly.

app/

modules/

user/

__tests__/

user.reducer.spec.js

components/

user.reducer.js

user.selectors.js <--- This is where all module selectors are exported

Prefix the name of your actions

I really advise you to define naming rules for your actions and if possible check them with an

eslintrule.

Actions are in uppercase letters separated by ‘_’.

Here an example with this action: SET_USERS.

app/

modules/

user/

__tests__/

user.reducer.spec.js

components/

user.actions.js <--- This is where all module action creators are exported

user.reducer.js

user.selectors.js

Action names are prefixed by the name of the module in which it is located.

This gives a full name: user/SET_USERS.

A big advantage of this naming rule is that you can easily filter the action in redux-devtools.

Always test your reducers

The reducers are the holders of your application’s business.

They manipulate the state of your application.

This code is therefore sensitive.

➡️ A modification can have a lot of impact on your application.

This code is rich in business rules

➡️ You must be confident that these are correctly implemented.

The good news is that this code is relatively easy to test.

A reducer is a single function that takes 2 parameters.

This function will return a new state depending on the type of action and its parameters.

This is the standard structure for testing reducers with Jest:

describe('ReducerName', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

// Init a new state

})

describe('ACTION', () => {

// Group tests by action type

it('should test action with some params', () => {})

it('should test action with other params', () => {})

})

describe('SECOND_ACTION', () => {

it('should test action with some params', () => {})

})

})

I also recommend that you use the deep-freeze package on your state to ensure that all actions return new references.

Ultimately, testing your reducers will allow you to easily refactor the internal structure of their state without the risk of introducing regressions.

Keep the immutability and readability of your reducers

A reducer is a function that must return a new version of the state containing its new values while keeping the same references of the objects that have not changed. This allows you to take full advantage of Structural sharing and avoid exploding your memory usage. The use of the spread operator is thus more than recommended.

However, in the case where the state has a complicated and deep structure, it can be verbose to change the state without destroying the references that should not change.

For example, here we want to override the Rhone.Villeurbanne.postal value of the state while keeping the objects that don’t change.

const state = {

Rhone: {

Lyon: {

postal: '69000' ,

},

Villeurbanne: {

postal: '',

},

},

Isère: {

Grenoble: {

postal: '39000',

},

},

}

// When you want to change nested state value and use immutability

const newState = {

...state,

Rhone: {

...state.Lyon,

Villeurbanne: {

postal: '69100',

},

},

}

To avoid this, a member of the Bedrock team released a package that allows to set nested attribute while ensuring immutability: immutable-set

This package is much easier to use than tools like immutable.js because it does not use Object prototype.

import set from 'immutable-set'

const newState = set(state, `Rhone.Villeurbanne.postal`, '69100')

Do not use the default case

The implementation of a redux reducer very often consists of a switch where each case corresponds to an action.

A switch must always define the default case if you follow so basic eslint rules.

Let’s imagine the following reducer:

const initialState = {

value: 'bar',

index: 0,

}

function reducer(initialState, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'FOO':

return {

value: 'foo',

}

default:

return {

value: 'bar',

}

}

}

We can naively say that this reducer manages two different actions. It’s okay.

If we isolate this reducer there are only two types of action that can change this state; the FOO action and any other action.

However, if you have followed the advice to cut out your reducers, you don’t have only one reducer acting on your blind.

That’s where the previous reducer is a problem.

Indeed, any other action will change this state to a default state.

A dispatch action will pass through each of the reducers associated with this one.

An action at the other end of your application could affect this state without being expressed in the code.

This should be avoided.

If you want to modify the state with an action from another module, you can do so by adding a case on that action.

function reducer(state = initialState, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'FOO':

return {

value: 'foo',

}

case 'otherModule/BAR':

return {

value: 'bar',

}

default:

return state

}

}

Use custom middlewares

I’ve often seen action behaviors being copied and pasted, from action to action.

When you’re a developer, “copy-paste” is never the right way.

The most common example is handling HTTP calls during an action that uses redux-thunk.

export const foo = () =>

fetch('https://example.com/api/foo')

.then(data => ({ type: 'FOO', data }))

.catch(error => {

// Do something

})

export const bar = () =>

fetch('https://example.com/api/bar')

.then(data => ({ type: 'BAR', data }))

.catch(error => {

// Do something

})

These two actions are basically the same thing, we could very well make a factory that would do the code in common.

Basically the meta action we want to represent here when it is dispatched:

Fetch something

-- return action with the result

-- in case or error, do something

We could very well define a middleware that would take care of this behavior.

const http = store => next => async action => {

if (action.http) {

try {

action.result = await fetch(action.http)

} catch (error) {

// Do something

}

}

return next(action)

}

// in redux store init

const exampleApp = combineReducers(reducers)

const store = createStore(exampleApp, applyMiddleware(http))

Thus the two preceding actions could be written much more simpler:

export const foo = () => ({ type: 'FOO', http: 'https://example.com/api/foo' })

export const bar = () => ({ type: 'BAR', http: 'https://example.com/api/bar' })

The big advantages of using middleware in a complex application:

- avoids code duplication

- allows you to define common behaviors between your actions

- standardize redux meta action types

Avoid redux related rerender

The trick when using redux is to trigger component re-render when you connect them to the state. Even if rerenders are not always a problem, re-render caused by the use of redux really has to be prevented. Just beware of the following traps.

Do not create a reference in the selector

Let’s imagine the next selector:

const getUserById = userId => state =>

state.users.find(user => user.id === userId) || {}

The developer here wanted to ensure that its selector is null safe and always returns an object. This is something we see quite often.

Each time this selector will be called for a user not present in the state, it will return a new object, a new reference.

With useSelector, returning a new object every time will always force a re-render by default. Doc of react-redux

However in the case of an object, as in the example above (or an array), the reference of this default value is new each time the selector is executed. Similarly for the default values in destructuring, you should never do this :

const getUsers = () => ({ users: [] }) => users

What to do then? Whenever possible, the default values should be stored in the reducer. Otherwise, the default value must be extracted into a constant so that the reference remains the same.

const defaultUser = {}

const getUserById = userId => state =>

state.users.find(user => user.id === userId) || defaultUser

The same goes for the selector usage that returns a new ref at each call.

The use of the filter function returns a new array each time a new reference even if the filter conditions have not changed.

To continue, it is important that useSelector does not return a function. Basically you should never do this:

const getUserById = state => userId =>

state.users.find(user => user.id === userId)

const uider = useSelector(getUserById)(userId)

A selector should not return a view (a copy) of the state but directly what it contains. By respecting this principle, your components will rerender only if an action modifies the state. Utilities such as reselect can be used to implement selectors with a memory system.

Do not transform your data in the components

Sometimes the data contained in the state is not in the correct display format.

We would quickly tend to generate it in the component directly.

const MyComponent = () => {

const user = useSelector(getUser)

return (

<div>

<h1>{user.name}</h1>

<img src={`https://profil-pic.com/${user.id}`} />

</div>

)

}

Here, the url of the image is dynamically computed in the component, and thus at each render.

We prefer to modify our reducers in order to include a profileUrl attribute so that this information is directly accessible.

switch (action.type) {

case `user/SET_USER`:

return {

...state,

user: {

...action.user,

profileUrl: `https://profil-pic.com/${action.user.id}`,

},

}

}

This information is then calculated once per action and not every time it is rendered.

Don’t use useReducer for your business data

Since the arrival of hooks, we have many more tools provided directly by React to manage the state of our components. The useReducer hook allows to set a state that can be modified through actions. We’re really very very close to a redux state that we can associate to a component, it’s great.

However, if you use redux in your application, it seems quite strange to have to use useReducer. You already have everything you need to manipulate a complex state.

Moreover, by using redux instead of the useReducer hook you can take advantage of really efficient devtools and middlewares.

Useful resources

- Use react with redux doc

- redux flow animated by Dan Abramov

- redux documentation about middlewares

- immutable-set

Thanks to the reviewers: @flepretre, @mfrachet, @fdubost, @ncuillery, @renaudAmsellem